I've long turned up my nose at sermons and related forms of mass moralizing.

One reason, quite simply, is that they bore me. Honesty good. Violence bad. My eyes glaze over. Empathy, rah! Racism, boo! Please, don't we know this already?

The other reason I've eschewed sermons is that I've never properly understood them. They live in one of those dark, uncharted regions on my map of human social behavior. Until recently, I mistook them for a grandiose form of nagging. "Now children," the preacher says, in a voice dripping with smarm, "be nice to each other." But this is off-putting: I don't want to be nagged, and I sure as hell don't want to be nagging others.

I've since come to realize that nagging is a cartoon model of how sermons are supposed to work. As a social phenomenon, they are incomparably more interesting than a parent admonishing a child. In fact, they bundle together a good number of my favorite social dynamics:

[Caution, here be spoilers]

Signaling, third-person effects, network effects, and common knowledge.

So today I want to explain how I've come to understand sermons and why I think they're a worthy subject. It still bothers me that so many of them are boring and devoid of first-order surprise — but we'll return to that in a minute.

Sermons

The archetypical sermon is what a preacher delivers from the pulpit: fire, brimstone, "love your neighbor," yada yada yada. But I'm not specifically interested in religious sermons. Instead I want to investigate the broadest, most general-purpose version of the phenomenon — the "Platonic ideal" (if you will) of a sermon. This will be much closer to what Phil Hopkins calls "mass moralizing." It's the kind of thing I can imagine an alien or AI society converging on: a pattern that emerges spontaneously under a few simple game-theoretic conditions.

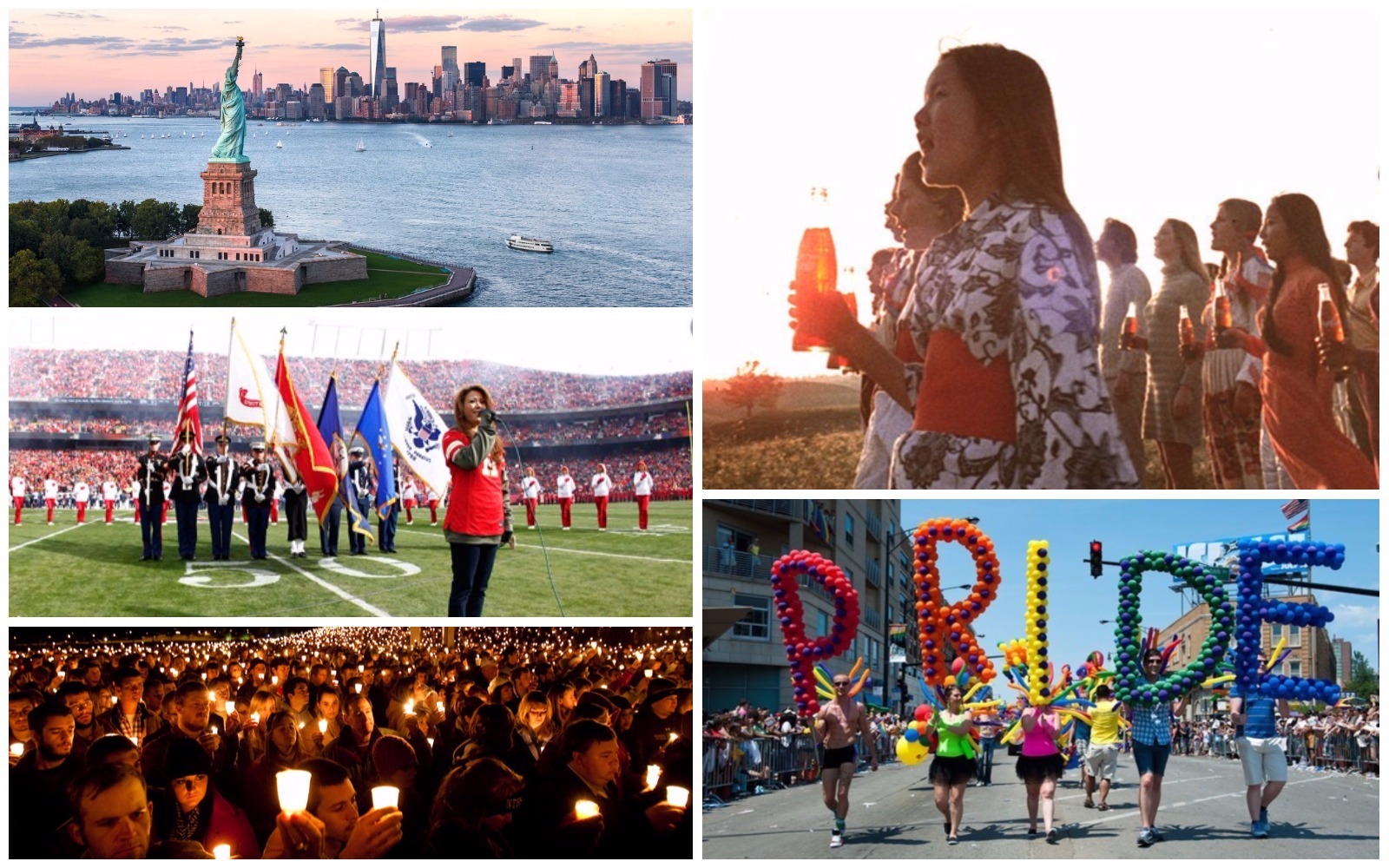

As I will use the term, then, a sermon is any message designed to change or reinforce what a group of people value. It might take the form of explicit exhortation, full of shoulds and shouldn'ts, oughts and mustn'ts. Or it may be entirely implicit, like the story of a selfless act that saves the day. Commencement speeches, TED talks, presidential inaugurations — whatever else they may be, all of these are at least part sermon because they attempt to change or reinforce our values en masse.

Moving beyond speeches, we also find 'sermons' in such unconventional forms as movies, charity balls, national monuments, and corporate mission statements. A sermon can be as elaborate as a parade or as straightforward as stating, "I believe in diversity" to a small roomful of people. Even ads can function as sermons. When Apple says, "Think different," it's urging us to value iconoclasm not unlike how a priest might ask us to celebrate chastity or compassion.

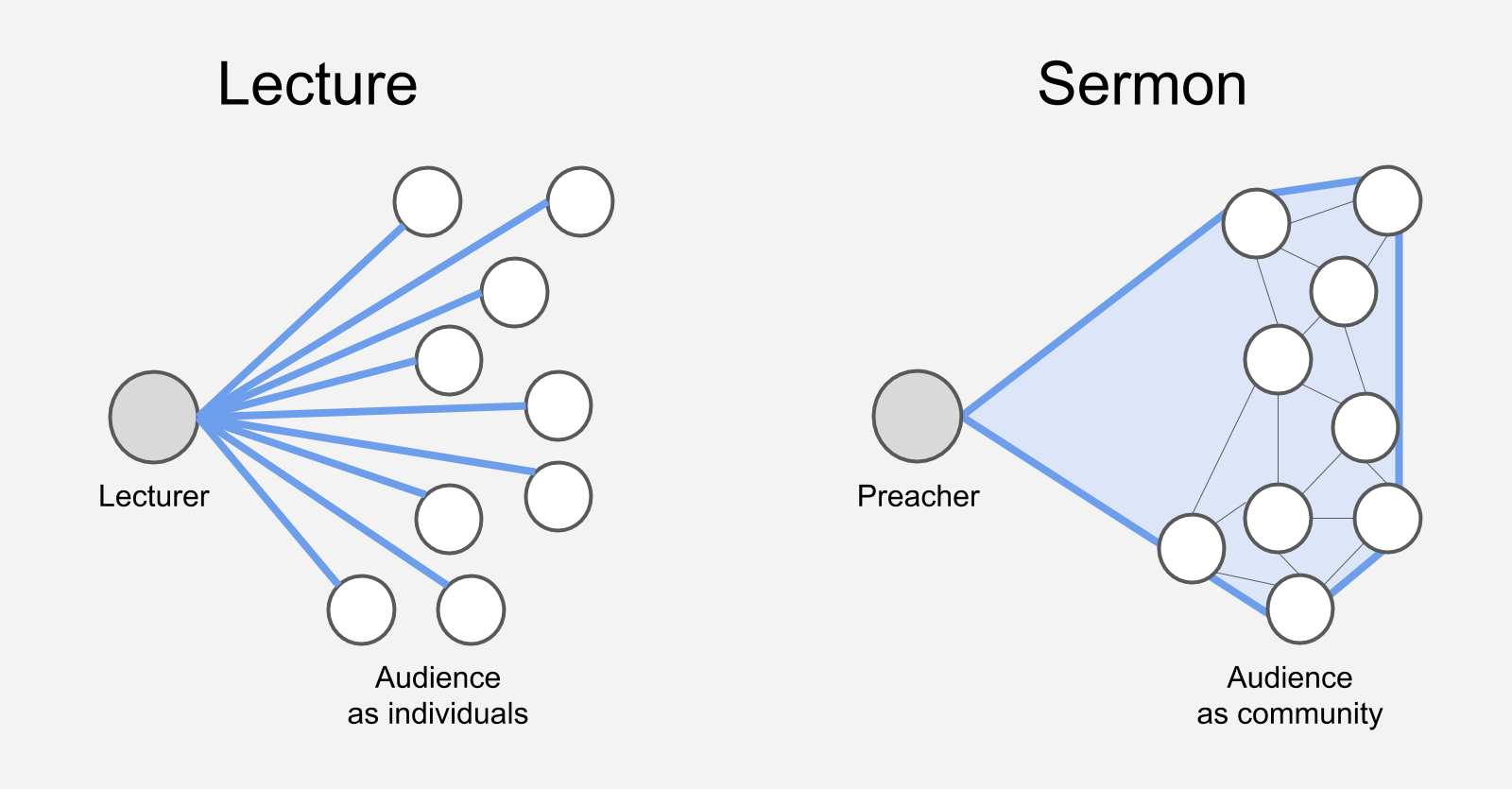

Now, to really get our heads around why sermons are interesting, it pays to contrast them with lectures. Both take roughly the same form: a one-to-many broadcast. But they have different functions (moralizing vs. imparting knowledge), and — please bear with me here — in order to fulfill these different functions, they require different topologies. Whereas a lecture addresses its "many" as a collection of individuals, a sermon addresses its "many" as an integrated community or flock: a network of listeners whose relationships stand to change by listening to the sermon:

Incidentally, you can literally see this topological difference when comparing a classroom to a church. In a sparse lecture hall, students will frequently sit apart from each other (but for the odd pair or threesome) — whereas in church, sparse or otherwise, congregants are encouraged to shake hands and introduce themselves to their neighbors:

But why? What's the crucial difference?

Suppose you and I are listening to a physics lecture. Although we share the same goal — learning physics — we're pursuing it more or less independently from one another (and from all other students in the lecture). If you happen to fail the class, it's no skin off my nose, and vice versa.

In contrast, suppose we're listening to a sermon — on the virtue of kindness, say. In this case, I do have a stake in whether you learn the lesson, because unlike physics, if you fail at kindness, I'm going to suffer. Put differently, there are positive externalities to the act of listening to a sermon. When you internalize a sermon's message, I stand to benefit, and vice versa.

An interesting corollary is that, as the audience shrinks, lectures degrade gracefully, whereas sermons get weird. Suppose Feynman's physics lectures were never recorded, and you were (somehow) the only person in attendance as he was delivering them. In other words, he's lecturing to an audience of one. Well, you might feel sad for everyone else who's missing out — but at least you'll learn some things, and Feynman is probably happy to teach you. (It might even be a competitive advantage for you to learn directly from the master.) But if you were somehow the only person at the Lincoln Memorial when MLK delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech... uh... awkward. Why is he using that voice when it's just you? Why is he wasting so much inspiration on a single listener? When you hear a speech like that, it only makes sense if you're sharing the experience with hundreds or millions of other people.

A simple sermon

Now, let's take a very simple sermon and examine it under the microscope.

Here's one that's as close to the Platonic ideal as we're likely to find (this side of the heavenly spheres):

Helen stands on a soapbox in the town square. "Friends, gather round!" she shouts through a bullhorn. "I have an important message for you. Peace is good! Peaceful people are virtuous and we should celebrate them. People who commit violence are evil and we should punish them. I implore you all, put down your weapons and be peaceful to each other!"

I think we all understand, at least intuitively, the effect this sermon is likely to have. If people appreciate what Helen is saying, they'll gather around her, continue listening, and become slightly more peaceful as a result.

But how, exactly, does this transformation occur?

One model that I've already dismissed is the nagging model: that the speaker uses her authority (moral or otherwise) to goad or coerce people into changing their behavior. This model sounds plausible if you're picturing the kind of sermon delivered in a medieval church, with a congregation held captive by an exceptionally powerful clergy. But if, instead, you imagine a presidential inauguration or commencement speech — or Helen's soapbox sermon in the town square — heavy-handed coercion stops making sense. Certainly some nagging takes place during some sermons, but it can't explain why people so often flock to hear them, happily and voluntarily.

Perhaps a more interesting model, and certainly a less patronizing one, is persuasion: that the speaker makes an argument which convinces her audience to change their behavior. Again, I'll grant that there's a role for persuasion in understanding how some sermons work, but I don't think it's nearly as big a role as many people think. Simple verbal persuasion — changing listeners' minds merely by exposing them to ideas — is too weak to have the kind of effects that sermons seem to have. Ideas by themselves, without carrots or sticks, are rarely persuasive enough to overcome entrenched (crony) interests.

(I realize not everyone shares this prejudice of mine, but we can save that full discussion for another day.)

So then, how are we to make sense of Helen's sermon in the town square? How does it induce people to be more peaceful? I have a model I'd like to propose — one that (no surprises here) makes heavy use of external social incentives.

Here are the main components (in bold):

To start with, Helen's sermon functions as a personal advertisement of her good qualities. By preaching, Helen essentially advertises that she's a peaceful person — or that she's at least trying to be peaceful. (If she preaches peace but doesn't practice it, she'll justly be called a hypocrite.) In other words, she's virtue-signaling, but not in a bad way. And other people will be drawn to her, then, in part by the promise that she'll behave well toward them.

In addition to advertising herself as peaceful, Helen also says (through her sermon) that she values peace in others, which implies that she's going to preferentially reward people for acting peacefully around her. Let's call this personal reinforcement. At minimum, she's offering her own friendship for those who are peaceful, and threatening enmity toward those who are violent. This incentivizes people to be peaceful in her presence, and in turn draws yet others into the fold.

As she endorses peace herself, Helen also seeks third-party endorsement from members of the audience. Note that she doesn't say, "I like peace," as if it were a subjective preference. Instead she says, "Peace is good," as a statement of objective fact. Audience members are thereby invited to endorse her sermon (e.g., by cheering, applauding, nodding along, or simply sticking around) or else reject it (e.g., by booing, heckling, or simply walking away). Everyone who sticks around and continues to listen respectfully is thereby acting to amplify the message. By their mere presence, the audience says, "We, too, value peace." And this density of peaceniks makes the environment even more attractive for others to join.

Meanwhile, since all these people are showing up, there's an important precondition that needs to be met: the value being preached needs to exhibit a network effect. In other words, the value needs to be such that the entire group benefits from each new person being added to it.

Peace certainly satisfies this criterion. Peaceful people get along smoothly with other peaceful people, while violent people gum up the works. P–P interactions are more productive and mutually beneficial (positive sum) than either P–V interactions or V–V interactions. In other words, when it comes to peace, the more the merrier.¹

This isn't the case with all values that one might conceivably "preach" to an audience. Suppose Helen promoted height instead of peace. "Being tall is good! Being short is bad! Everyone should wear lifts!" While this could conceivably function as a self-help lecture — arguably, some individuals should wear lifts — it makes for a terrible sermon. Specifically, there's no benefit for a whole group to convene to celebrate height, because groups don't typically benefit by preferring tall people and excluding short people. Height, unlike peace, doesn't have a network effect.

Diagrams

A proper sermon, then, is an attempt to cultivate a network effect around a shared value — and the preacher herself acts as a seed around which the network crystallizes.

Thinking about this visually has been really helpful to me, so I wanted to share a few images I made to convey the dynamics I have in mind. The core idea is that a sermon warps the social fabric in ways that encourage virtue and discourage vice.

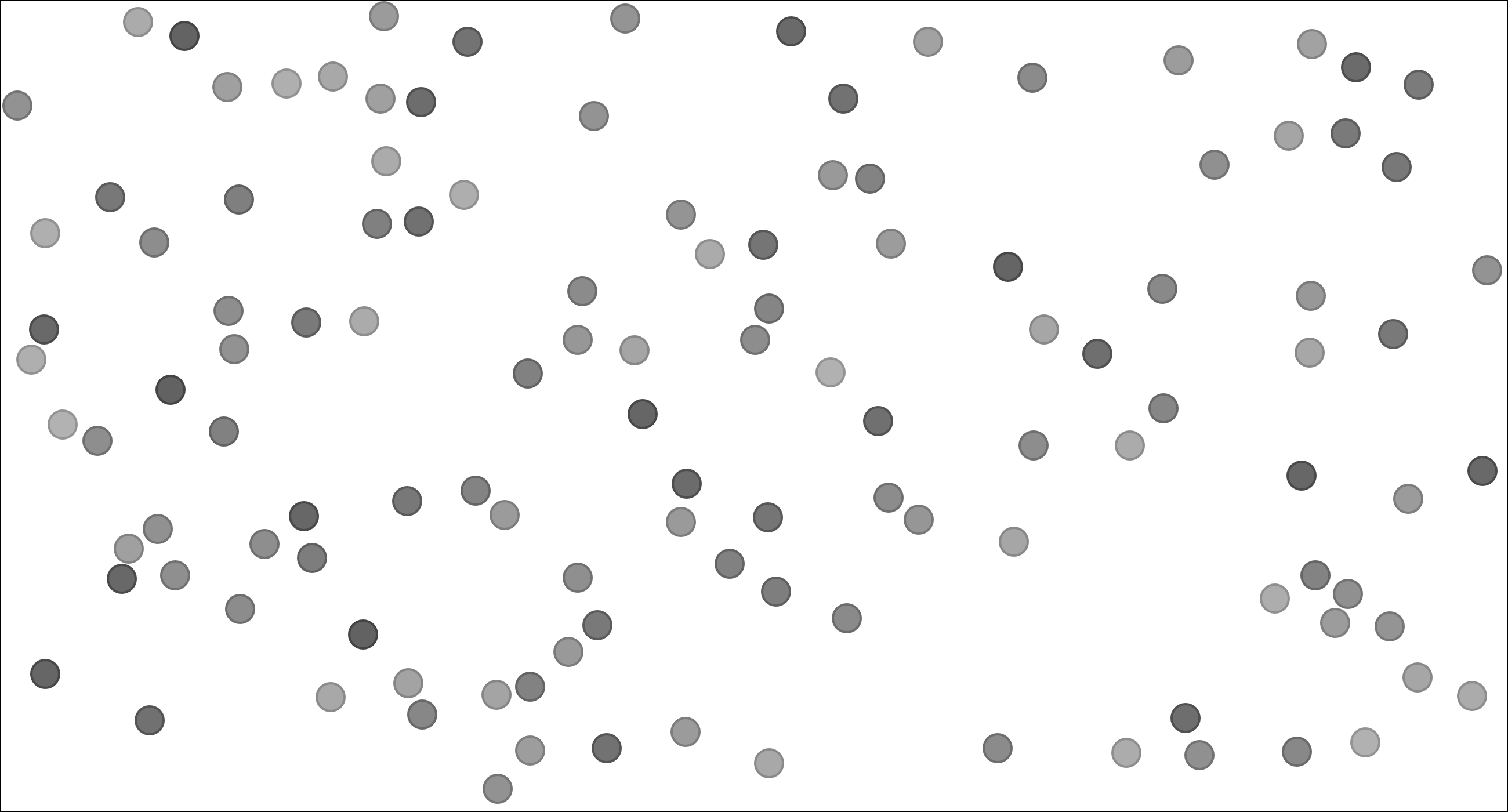

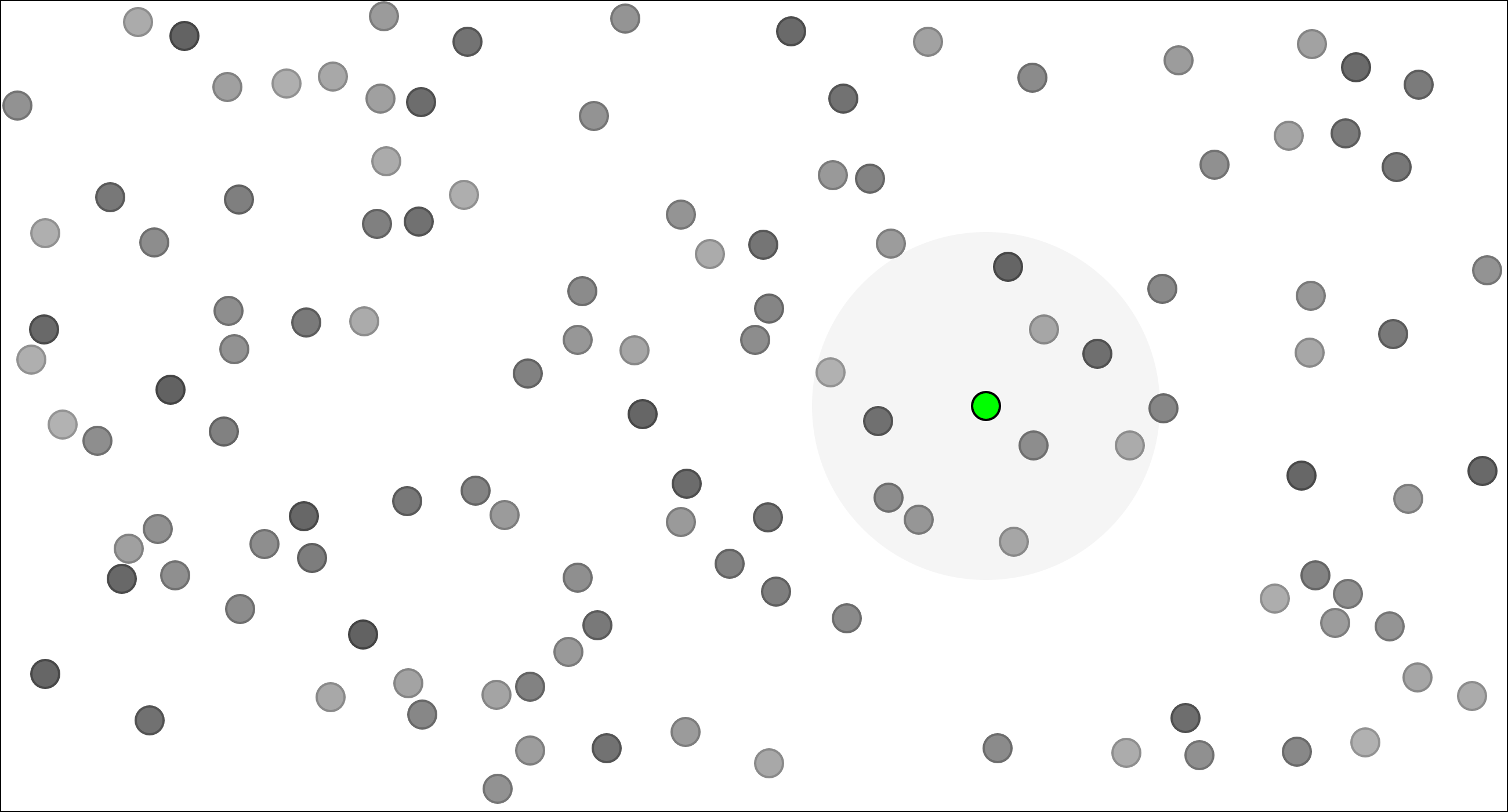

To start with, here are a bunch of people milling around the town square, more or less minding their own business:

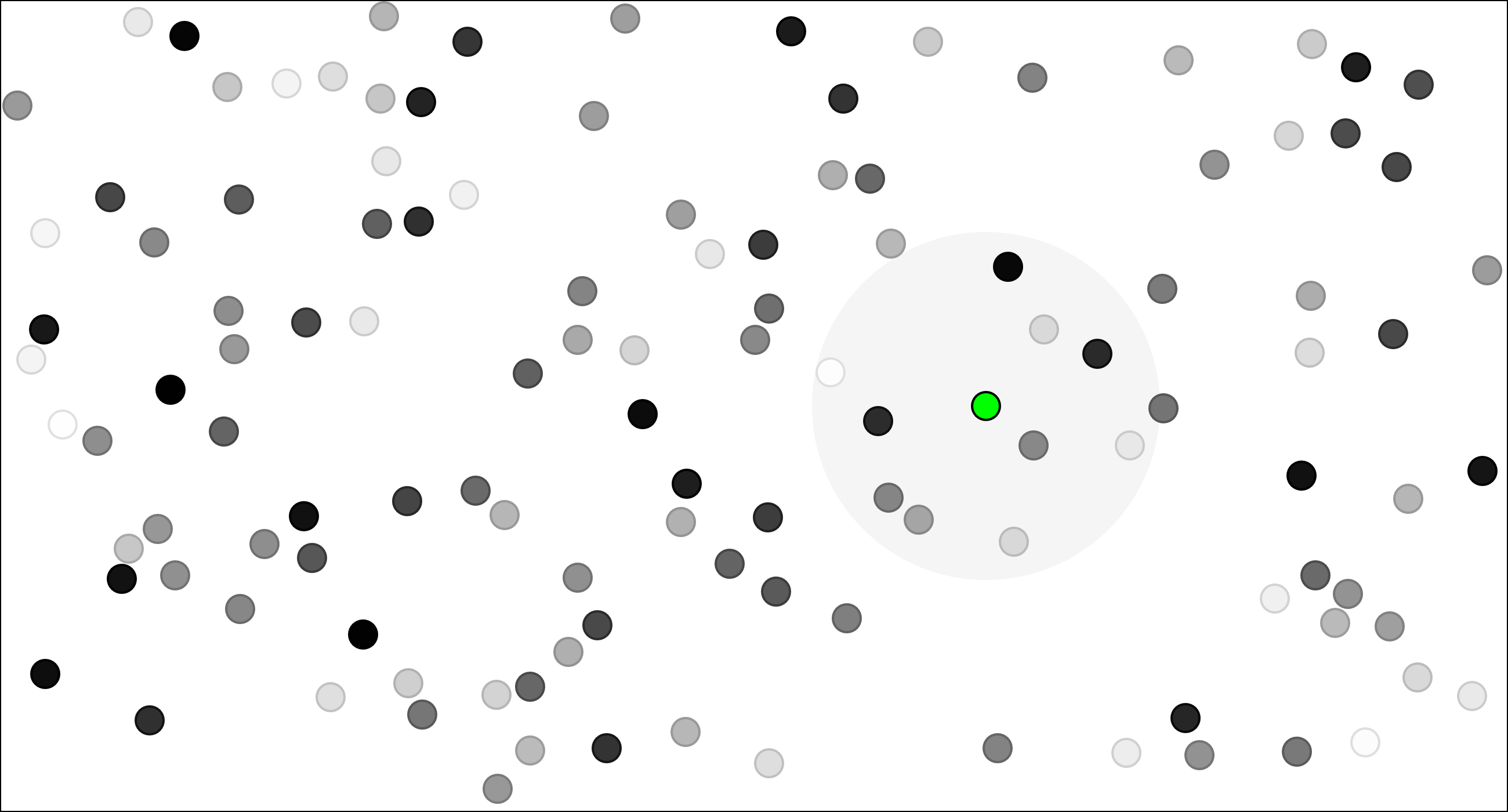

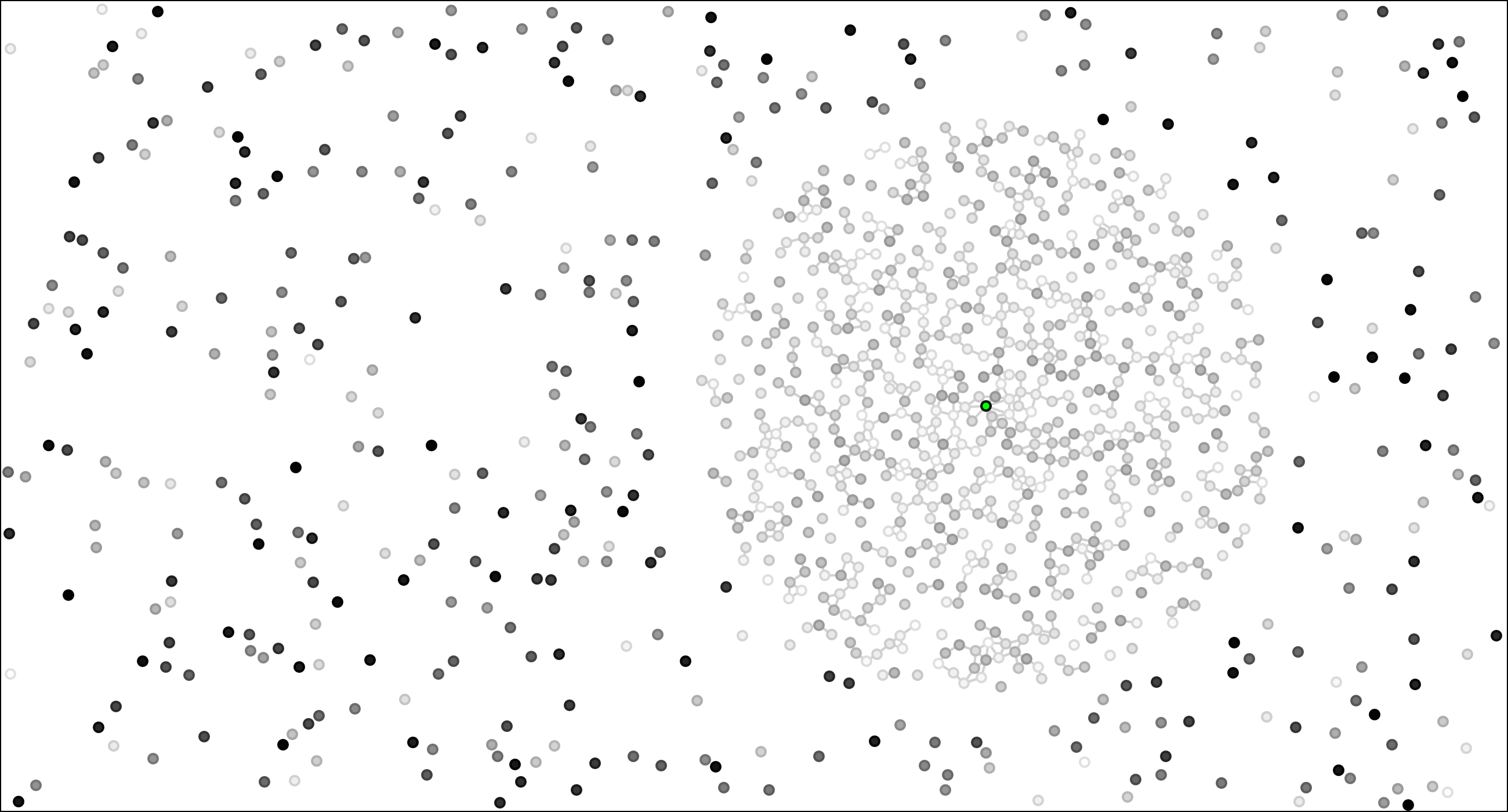

At some point, Helen (in green) gets on her soapbox and starts preaching about peace:

Soon, everyone becomes attuned to how peaceful or violent everyone else is; it becomes an especially salient factor in the town square. In the diagram below, lighter is more peaceful; darker, more violent:

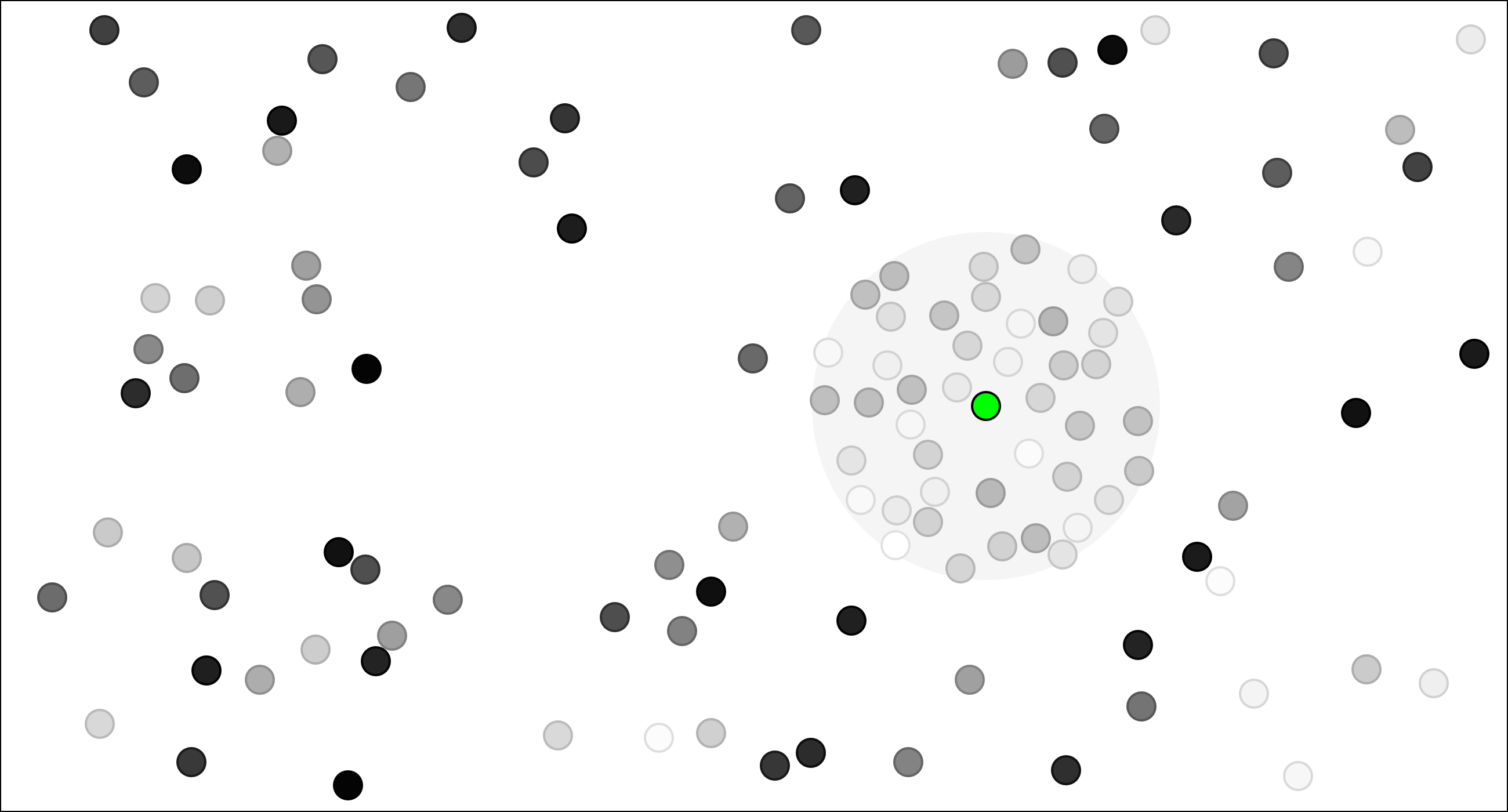

As Helen continues preaching, the space around her becomes more rewarding to those who act peacefully and less rewarding to those who commit violence (for the reasons we discussed above). Thus, peaceful people start to pool around her, within earshot, while violent people steer clear. Additionally, some listeners may make an effort to change their behavior and act more peacefully than they would otherwise. The net effect is that the audience becomes statistically more peaceful than the rest of the town square:

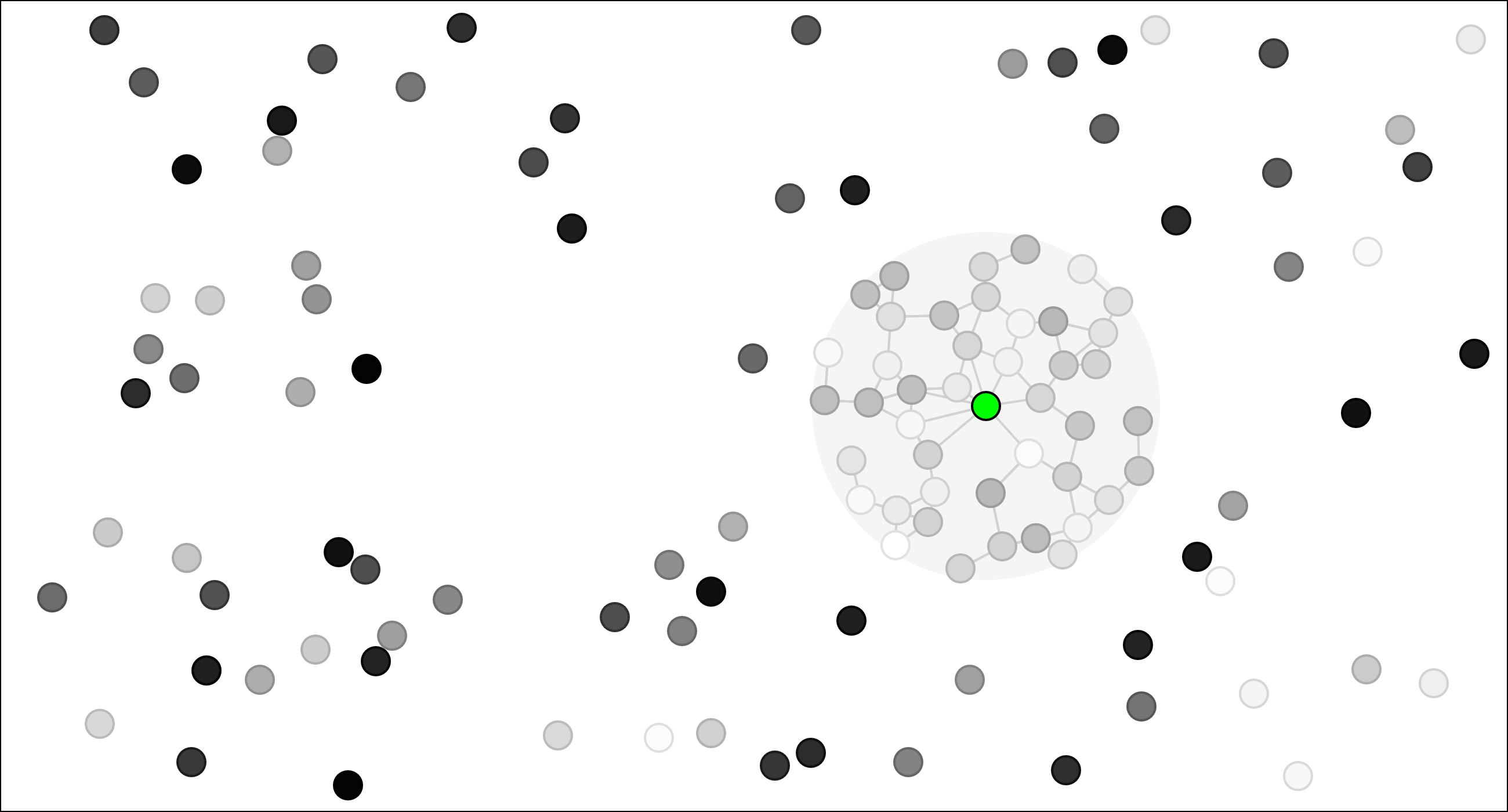

Having been drawn together, people will then be eager to form and strengthen relationships with others inside the sermon bubble. Friends who already know each other will be happy to learn that they share a common value, while strangers can feel good about meeting each other under the auspices of peace. Even if audience members don't make contact during or after the sermon, they'll at least take note of the other faces in the crowd, the better to recognize them later down the road. ("Didn't I see you at Helen's sermon? You must be one of the good people.") However it happens, the result is a stronger network²:

A minimal success for Helen would be to make a peace-loving friend. A maximal success would be if her sermon catalyzed an entire movement, not unlike those launched by Gandhi or MLK. In practice, of course, most sermons are far too weak to summon a coherent superorganism. But this is nevertheless the kind of thing sermons are attempting to do:

However large the audience, eventually it will disperse. But the boost to these relationships will linger for days or weeks, potentially even a lifetime. All of which is astonishing: with just a few choice words, a preacher can create social capital out of thin air.

Common knowledge

Now, there's one final component to a sermon that I neglected to mention earlier. (It's meaty enough that I wanted to save it for its own section.) In addition to the other components — personal endorsement from the preacher, third-party endorsement from the audience, and network effects — a sermon also needs to produce higher-order or common knowledge.

This means it's not sufficient for everyone in the audience to hear and grok a sermon individually, as it is with a lecture. Instead, for maximal effect, everyone has to know that everyone else has heard and grokked the sermon as well. The more thoroughly this kind of knowledge saturates within a community — everyone knowing that everyone else knows that everyone else knows that... everyone understands the sermon — the stronger the resulting network.

Why?

I think it largely comes down to the difficulty of enforcing standards. Sure, Alice and Bob might both individually endorse the importance of forgiveness, say. But if Alice doesn't know that Bob also endorses forgiveness, it's much harder to hold him to it. If she sees him being vengeful, she might think, "Well, he just doesn't know any better." From Bob's perspective, he's less likely to misbehave if he attended the sermon and knows that Alice saw him there. His awareness of her awareness will give him second thoughts about acting badly. In addition, moral communities often benefit from upholding a so-called meta-norm: an injunction to punish anyone who doesn't punish others for their transgressions. As you can imagine, this kind of recursive rule requires commensurately recursive knowledge in order to get off the ground.

The need for a sermon to generate common knowledge helps explain a lot of typical features:

- Sermons are usually delivered in public, where people can listen together. Gossip, though it also aims to convey moral information, is conducted in private, and therefore fails to generate the same kind of network effect as a sermon.

- Sermons can't be shy; they benefit from being conspicuous.³ There's a reason Helen stands on her soapbox and uses a bullhorn. The whole point is to reach people and give them confidence that others have heard the sermon as well. To this end, it's important for a sermon to be clear and loud, but also entertaining, memorable, quotable, etc. All else being equal, a boring sermon is less effective than a captivating one.⁴ When the audience is half-asleep, it breaks the common-knowledge spell.

- Sermons need to be repeated. This is because real human beings — unlike the hyper-rational archetypes contrived for use in logic puzzles — need to hear a sermon more than once in order to understand it, remember it, and infer all its consequences. Even if you can understand a sermon after hearing it for the first time, others might need more time and repetition. Nothing becomes common knowledge in a large population without a fair bit of harping. This helps explain why preachers often repeat key phrases within the same sermon, and why churches return to the same themes year after year after year.

- Generally, a sermon shouldn't be elitist; it should appeal to the widest tastes and/or lowest common denominator. The more people it reaches, the better — so it should strive not to alienate anyone, and its message should be easy and palatable enough for most listeners to digest. If a lecture on quantum mechanics is so difficult that some students struggle to comprehend it, that may actually be a feature — but for a sermon, inaccessibility is almost always a bug.

- A sermon feeds on audience participation. At a minimum, people need to show up in order to see and be seen by each other; their attendance itself is an important form of endorsement. Beyond that, cheers and applause help generate common knowledge of how strongly different parts of the sermon are endorsed. The louder and longer the cheer, the more obvious it is that everyone's on board — and that they all know it. Songs, group chants, and call-and-response patterns all help generate this kind of common knowledge. Laughter also works extremely well, as long as it's not the divisive kind of laughter (e.g., the audience laughing at the speaker).

Now, at least two of these features are in tension with each other. As we've seen, the ideal sermon is both captivating and repetitive. But repetition is boring. Instead of holding the audience's attention, a repetitive sermon risks alienating it.

I suspect most of my readers are like me, in that we gravitate toward novelty and recoil from repetition. (Are you also bored by sermons, or is it just me?) Part of my problem, I suspect, is that I fixate on the wrong things. I'm constantly asking myself, "Did I know this already?" and coming up disappointed, when instead I should be wondering, "Who else is in the audience, and did I already know that they knew this?" In other words, a sermon might be entirely obvious, redundant, and boring at the object level, while at the same time generating novel, valuable information at higher-order levels.

And yes, a sermon I've heard a dozen times might still be boring, but at least I find comfort in knowing that it isn't pointless.

One especially repetitive type of sermon that I've recently come to appreciate is the wedding. Aside from its effect on the couple at the altar, each wedding also serves to reinforce the institution of marriage among everyone in the audience. Remember, marriage isn't just a promise between two individuals. It relies on a whole complex of norms⁵ supported by an entire community.

Over the course of our lives, each of us attends a good number of weddings (including those on TV and in movies), and all that preaching really adds up. But imagine a world in which weddings weren't nearly as common. Suppose 'marriage' was as exotic to you as the relationship between serf and feudal lord. Sure, you might understand the basic outline of the institution, but you'll be hazy on specifics and you won't really feel the moral weight of it in your bones. In such a world, would you instinctively know to treat other people's marriages as sacred? Would you urge your married friends to stick out their rough patches? Would you hold stigma in your heart for someone who casually broke off their own marriage, or who attempted to seduce a happily married partner?

Every wedding sermon delivers more or less the same message: love is wonderful and marriage is a serious, lifelong commitment. And we need this repetition; it's the very care and feeding of the institution. Every wedding, no matter how uninspired, replenishes higher-order knowledge and reinforces the network effect. And simply by attending, the guests are celebrating not just the happy couple, but also the very idea of marriage itself.

Sermons in strange places

One of my favorite sermons of all time is a blog post: In Favor of Niceness, Community, and Civilization by Scott Alexander over at Slate Star Codex. You should go read it when you're done here (the end is near, I promise!), but the actual content isn't relevant to our concerns. What's important is the format.

Now, ordinarily, a blog post isn't a great format for a sermon — but then Slate Star Codex is no ordinary blog. It happens to be everyone's favorite blog, at least in my little corner of the internet. Whenever I meet someone new and learn that they're a fellow reader, I think, "Ah, this is my kind of person." The discussion section for each post brims with substantive comments that routinely number in the hundreds, occasionally in the thousands. Like weekly church service, SSC is a place to see and be seen, and therefore a place to generate higher-order knowledge.

I'm pretty sure I would read Slate Star Codex even if no one else did. But when one of his posts delivers a moral message, I'm especially glad so many other people are reading it along with me. And since Scott is such a clear and charismatic writer, people typically read the whole thing (and often remember it!), even when it's a long and complex argument. He pools attention exceptionally well, and uses it not just to educate, but to help his readers connect over shared values.

This is the same way that a book or movie can function as a sermon. It's not necessary to physically sit next to others while you're experiencing it, as if you were in the pews at church. Instead, there's something of an ad hoc forum that develops 'around' the work in question — think dinner-party discussions, water-cooler talk, and subreddits full of gushing fans — analogous to the earshot-zone around Helen in the town square. Wherever people bond over shared values sparked by a piece of art, there's a sermon in action.

So if a movie, book, or blog post can function as a sermon, what about a tweet?

Absolutely. After the recent spate of demonstrations by white nationalists, Barack Obama tweeted:

No one is born hating another person because of the color of his skin or his background or his religion.

This quickly became one of the most popular tweets of all time. In just a few days, it racked up 1.7 million retweets and 4.6 million likes. And yet, of all the people who liked and retweeted it, how many of them actually learned something new? Everyone in that audience already knows that racism is wrong. But what people may not have realized is how many others stand against racism alongside them — as well as, perhaps more importantly, which particular others stand with them. This is a valuable service, not to be shrugged off as obvious or redundant.

I picture each of these viral tweets as an impulse flashing across a graph of users. Every like and retweet is an endorsement, a tiny cheer for a miniature sermon. And each endorsement, in its small way, enhances the relationship between two or more people, uniting them as champions of the same cause. As one of these tweets propagates, the network tightens along its wake — almost imperceptibly, to be sure, but the effects add up. Taken altogether, tweets, like sermons, bring people together.⁶

And this, I'm a bit sad to report, is why outrage is so contagious. Outrage is like the angry, pitchfork-wielding cousin of the more conventional, respectable type of sermon. But it's a member of the sermon family nonetheless, and therefore subject to all the dynamics we've discussed here today.

On the internet, we love to share the outrage du jour, while older forms — just as popular in their heyday — include effigy burnings and public executions. These are roughly the double-negative of a positive sermon: By raging against a vice, you elevate its opposing virtue; by condemning Evil, you celebrate Good. And although outrage has some serious downsides, like all sermons, it can be very effective at bringing a moral ingroup closer together.

A final thought

If there's any kind of lesson in all this, it's mostly some advice I want to give myself.

The lesson is simply: speak up.

It's OK to slip into advocacy now and then, so long as you do it tastefully. If it sounds high- or heavy-handed — or anything like nagging — you're doing it wrong. Just explain why you care about a particular value. The goal isn't to change individual behavior (at least not directly), but rather to cultivate a network effect. And who doesn't like a network effect?

Moreover, there's no need to preach the very highest or most important ideals. Peace, love, and compassion have been glorified ad nauseam; they're already fully saturated as common knowledge. A better approach is to focus on values that are underappreciated — whatever you would personally like to see more of, both in yourself and the people around you. Preach the network effect you wish to join in the world.

Perhaps a metaphor will help. Delivering a sermon, I think, is a bit like planting a flag and setting up camp. It's an invitation to others: come, join me, it's safe and friendly around here. One strategy is to settle in with a big camp that will accommodate hundreds (or hundreds of millions) of people. Or maybe you'd prefer to huddle around a small campfire with a few close friends. That's nice too, as long as there's reason to gather.

Where do you want to hang your hat and lay your head? Is it good for others to join you? There's your sermon; let them hear it.

———

Further reading:

- That Slate Star Codex sermon on niceness and civilization.

- Robin Hanson on mass moralizing.

Endnotes:

¹ Peace has its limits, of course: a tribe can't be so peaceful that they forget how to fight other tribes.

² Note that not everyone benefits from Helen's sermon. In particular, the strong, aggressive, or dominant types might prefer if Helen had never stood on her soapbox, because they'll either be left out in the cold or be forced to behave more peacefully than they're otherwise inclined to.

³ Note from the Etymology Fairy: conspicuous derives from the Latin com-, meaning together, plus specere, meaning to observe (cf. spectacle). What is conspicuous is something that is easily noticed, and therefore noticed by everyone. A more Germanic construction might be "togetherseen."

⁴ Actually, it's not entirely true that boring sermons are necessarily less effective than captivating sermons, because there's a costly signaling dynamic going on. In some cases, we can get greater commitment to our shared values by attending a boring sermon, because those who are willing to endure the boredom are the real die-hards. In other words, boredom is sometimes a feature rather than a bug.

⁵ A "normplex," perhaps?

⁶ Not every tweet functions as a sermon, of course. Many tweets are educational, for example, and these have a different effect on the social fabric.

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt