Over the past few weeks I've been writing about how humans develop their social personalities.

As usual, the writing process helped me see things more clearly. In particular, I realized that the same model that explains human social personalities can be used to explain three other types of 'personalities':

- Human non-social personalities

- Personalities of non-human agents

- Generalized sexual strategies

You can refresh yourself with Part 1 and Part 2 of the series, but they're a bit long, so here's a summary of what we covered:

Personality is what happens when you take a general-purpose reinforcement learning algorithm, attach it to an agent seeded with some basic tendencies, and set it loose in a social ecosystem. What the agent learns is a strategy for succeeding in the world, based on its own strengths and weaknesses as well as the constraints of the environment. This learned strategy is what we call personality.

The key takeaway here is that personality is a function of the fit between agent and ecosystem. In other words, each (agent, ecosystem) pair is capable of producing a distinct personality.

Now watch what happens when we slot in different types of agents and ecosystems.

Professional and political personalities

As a student, you might suppose that a teacher who's bossy in the classroom is also bossy at home and among his friends. But in doing so, you'd be committing the fundamental attribution error — the well-documented tendency (read: bias) to underestimate the effect of the environment in determining how someone behaves.

The error arises because we intuitively model personality as a function of an agent in isolation, rather than an (agent, ecosystem) pair. In this case, the (teacher, classroom) pair gives rise to a bossy personality, while the (teacher, social life) pair might give rise to something else.

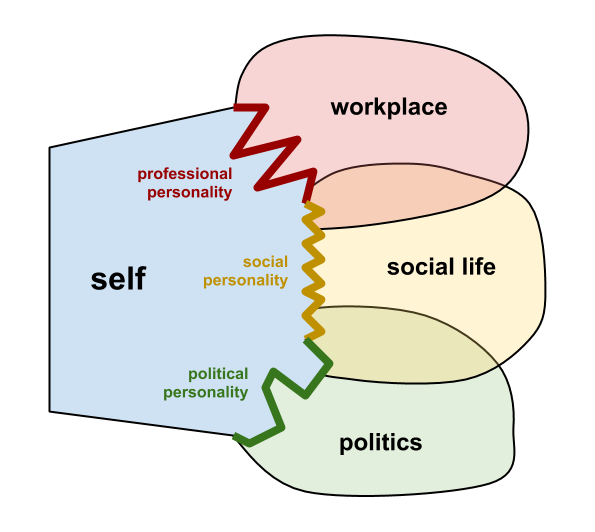

If we fix the agent, we can ask how different ecosystems produce different personalities. Human agents inhabit at least three different types of ecosystems:

- The social ecosystem, which produces a social personality.

- The workplace ecosystem, which produces a professional personality.

- The political ecosystem, which produces a political personality.

Each ecosystem is its own 'game', and every game of course requires its own strategy. For a given agent, the optimal strategy in the social game will differ from the optimal strategy in the professional game, which will also differ from the optimal strategy in the political game.

These games/ecosystems aren't mutually exclusive, but they're distinct enough to be worth considering separately. A woman who's kind, gentle, and nurturing at home and at church (with her family and friends) can at the same time be ruthless at her office — without suffering any cognitive dissonance. To the extent that the ecosystems overlap, the different facets of personality will also overlap, but to the extent that the ecosystems are separate, the facets may diverge.

I explored some of these ideas in an earlier essay, The Ecology of Personal Politics. I explained how we develop our political beliefs and behaviors — i.e. our political personalities — by finding the best strategy given (1) our natural dispositions, and (2) the political environments in which we are 'socialized.' The same phenomena that explain how we develop our social personalities — niche selection, adaptation, and construction — also explain how we develop strategies for navigating the political realm.

As an aside, I find it interesting that politics induces an error that's (in some sense) the opposite of the fundamental attribution error. Behavior is always a function of (agent, ecosystem) pair. Typically we underestimate the effect of the ecosystem, but in politics we underestimate the effect of the agent.

To play the political game, we're forced to argue about what's right or wrong for the entire system, but we typically form beliefs about the world based on what's right or wrong for ourselves (as individuals within the system). People who lean libertarian, for example, would almost always benefit if the world were organized according to libertarian principles, but it's hard for them to model what it's like for others, who might not benefit in the same ways (or benefit at all).

Personality in non-human agents

It's not only humans who can develop personalities. Personalities arise in any complex process that needs to learn a decision-making strategy based on feedback from its environment. In other words, the same game theory and learning algorithms that drive personality development in individual humans also drive strategy in larger collectives.

Companies, for example, are complex decision-making processes. They operate in an ecosystem that includes customers, other companies (as competitors, clients, vendors, and partners), and employees (both actual and prospective). And companies certainly have personalities. Anyone who's flown Virgin has experienced an airline with a distinct personality.

It's the same mechanism — reinforcement learning — that explains how companies and humans develop their personalities. In Part 1 of this series I mentioned SWOT analysis, which is a tool for reasoning explicitly about the factors that determine an optimal strategy. But reinforcement learning works whether or not the reasoning is made explicit/verbal. As long as a company is able to perceive feedback from its environment and adapt its decision-making and behavior — to do more of what works and less of what doesn't work — it will converge on a strategy that's at least locally optimal.

Companies and people also have a similar structure to their personalities. Both have a 'true'/internal nature (which dictates how they actually make decisions) as well as an external face. For people, the external face is the persona, and for companies it's their PR, marketing, and sales departments. These organs of the corporate body all strive to put the best, most consistent face (and verbal spin) on what is actually a very messy and haphazard internal decision-making process.

And the same way humans develop different personalities for different ecosystems (social, professional, political), companies also have different personalities/strategies for each of the games they play. Apple, for example, is shiny and friendly toward consumers, dominant and aggressive with suppliers and partners, and relatively indifferent toward potential employees (relying mostly on their consumer image and fanboyism to drive interest among recruits).

What holds for people and for companies also holds for nations. A nation is a vast enterprise, but it's still an agent capable of learning from feedback, and it still sits within an (even larger) ecosystem, i.e., the system of inter-national relations. Many of the same phenomena that play out for people and companies also play out for nations — just at much longer time scales.

Generalized sexual strategies

To the extent that men and women differ in the types of personalities they develop, we can ask where those differences come from.

Clearly the social ecosystem plays a big role. Whether we like it or not, there are different niches for men and women in society, so it's natural that those niches will influence the strategies people develop in adapting to them.

Just as clearly there are genetic differences between the sexes (i.e. the Y chromosome). Whether or not those differences contribute to building slightly different types of brains, they certainly contribute to building different types of bodies. So to the extent that our bodies influence the development of personality (as I argued earlier), the differences in male/female body types will contribute to different male/female personalities.

But what I find most interesting is how personalities are shaped by the different incentives men and women face when it comes to sex. In particular, women pay a much greater cost in bearing children, and (separately but relatedly) female fertility is often the rate-limiting factor in reproduction. [1]

These different incentives give rise to different sexual strategies. (We might consider this another facet of personality: a 'sexual personality' to sit alongside our social, professional, and political personalities.) Historically — especially before birth control — men were more interested in pursuing short-term mating opportunities, whereas women had to be more careful about when and with whom they had sex. And since female fertility was a scarce resource, women could afford to be choosy (at least when their social systems weren't treating them as property of their fathers or husbands).

But I'm not interested in the particulars of men, women, and sexual intercourse — and I'm definitely not interested in the very messy details of how societies have influenced these things. Instead I want to look at this problem in more abstract terms, to see where else it applies.

Here's an extremely simple model of the human short-term mating game. Given two different types of agents (M and F) and an act (S) that requires one of each type of agent:

- Differential cost: S has the potential to benefit both agents, but costs more for F agents than it does for M agents.

- Female scarcity: F agents are limited in their ability to engage in S acts (relative to M agents).

This model applies to more than just Males, Females, and Sex. For example, we could try M = car dealership, F = customer, and S = buying a car. Are the criteria above satisfied in this case? Yes. Differential cost is satisfied, since buying a car is very expensive for the buyer, but costs only time and effort on the part of the dealership. Female scarcity is also satisfied, because a customer buys a car only once every few years, whereas a dealership can sell as often as they're able to find buyers.

So we should expect, then, that car dealers will pursue a "male" sexual strategy (or personality) while buyers will pursue a "female" sexual strategy. It's not obvious what this means, exactly, but here are some educated guesses:

- Dealers will advertise (as in most species the male puts on more conspicuous displays).

- Dealers won't be terribly choosy about their buyers.

- Dealers will devote more energy to closing deals, and will act more urgently and insistently.

- Buyers will take their time and shop around before they commit to buying.

- Buyers will be more discriminating.

- The choice of whether to buy ultimately lies with the buyer.

It's no coincidence that car salesmen are often characterized as sleazy: it's because they face the same incentives as men in night clubs, and adopt a similar strategy.

But there's nothing particularly special about cars — they're just a big-ticket item, so all the behavior is exaggerated. Across all types of retail, sellers adopt a male strategy and buyers a female strategy. The hallmarks of the male strategy are advertisement and urgency, while the hallmarks of the female strategy are discrimination and choice.

Where else do we find this pattern? It's been especially interesting to me to watch the Silicon Valley ecosystem shift back and forth between

Entrepreneurs:Male :: Investors:Female

and

Entrepreneurs:Female :: Investors:Male.

These patterns track the ebb and flow of the tides of money. When money is scarce, investors adopt more of a female strategy, and entrepreneurs respond with more of a male strategy. When money flows freely, the strategies are reversed.

A year ago, Jason Freedman at 42Floors wrote a wonderful blog post titled The pendulum has swung. It explained how the financial climate had changed (seed-funding money had become abundant) and offered some observations about how entrepreneur and investor behavior had to adapt:

The feeling was palpable. Y Combinator had sixty-five companies present (42Floors was one of them). And we saw 500 eager investors, frenzied almost, excited to invest in entrepreneurs. One investor emailed me four times, texted me three times, called me and sent me a message on LinkedIn — desperate to get a check in before the round closes....

Slow It Down.... you have plenty of options and you don’t technically need their money. Choose carefully. You want to really know each other.

In the climate described here, money is flowing freely, so investors adopt the male strategy (insistence, urgency) while entrepreneurs adopt the female strategy (slowing it down, being choosy).

Freedman contrasts this with an even earlier time, when money was scarce:

Let me take you back to Y Combinator demo day, summer of 2009. We launched FlightCaster. I have this distinct memory of standing in the lobby, seeing these investors talking to each other. I sheepishly introduced myself, giving them the 30-second pitch on FlightCaster. They weren’t rude, they weren’t abusive, but they weren’t hungry to talk to me.

Note that in 2009, entrepreneurs (M) had to initiate courtship, while the investors (F) had the luxury of being choosy.

Strategies can shift even between different rounds of funding. Currently the Silicon Valley ecosystem is experiencing a glut of seed-funding money and a shortage of "Series A" money (the so-called Series A crunch). Entrepreneurs who raised a seed round a year ago were socialized in an environment where they could pursue a female strategy, but now face a different financial climate that demands more of a male strategy. Many will be able to adapt, but many will have a hard time changing their fundraising 'personalities' so quickly.

Of course, the game being played by investors and entrepreneurs is much deeper than this simple analysis would suggest — but then, so is the human mating game. Here we've only been considering short-term mating; everything gets much more interesting when you add in the potential for forming longer-term pair bonds.

In fact, the richness of the human mating game is why it's such a prominent metaphor in business settings. We use sex the same way we use all metaphors: to reason about an abstract target domain (forming business partnerships) in terms of a more familiar source domain (dating, getting married, etc.).

It's something to think about the next time you meet with representatives from another organization. Who's looking for a short-term mating opportunity? Who's looking for a long-term relationship? Are you playing the low-status male trying to seduce a high-status female? Are you a low-status female being wooed by a high-status male for a once-and-done encounter? Are you the young girl in her prime, or the old maid looking at her last chance at marriage? Do you get to be choosy, or should you be acting more urgently and aggressively? Etc. etc.

The more accurately you can model your situation in terms of the human mating game, the more you'll be able to engage your instincts and narrative faculties in helping you figure out how to act.

___

Endnotes:

[1] Added 2015/03/19: Maybe the two phenomena aren't so separate. C.f. Bateman's principle which states that "the sex which invests the most in producing offspring becomes a limiting resource over which the other sex will compete."

Melting Asphalt

Melting Asphalt